September 28, 2020

Livi Gerbase is a policy advisor at the Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos (INESC), a non-governmental, non-profit, non-partisan organization based in Brasília, Brazil. For 40 years, INESC has been working with partner organizations of civil society and social movements to raise a voice in national and international forums for public policy and human rights discussion, always keeping an eye on the public budget. INESC believes that understanding and interpreting this budget is a fundamental part of promoting and strengthening citizenship and guaranteeing the rights of all citizens.

As of July 17th, with over two million cases and 77,851 deaths, Brazil became the country with second most coronavirus cases in the world, only exceeded by the United States. We have been at a plateau of an average of thousand deaths per day for some weeks now (our new normal). In spite of these drastic and horrifying numbers, the governors of the most affected states are starting to allow the reopening of establishments and encouraging people to stop quarantining. Recent research from PUC-Rio has shown that Black people and those with lesser amounts of education have higher fatality rates than white people with less education - not surprising data for one of the most unequal and racist countries in the world.

In light of this health and economic crisis, economic policy issues have been in the center of the political debate. In Brazil, unfortunately, the discourse around post-COVID-19 recovery has always been the priority for the government, which has been detrimental to taking the new coronavirus seriously. According to our president, it is just a little cough that can be easily dealt with hydrochloroquine, neither of which is true.

The need to mobilize further government spending and put the needs of the people at the front of fiscal equilibrium has shaken the dogma of some economists, influencers and decision-makers. The question that has surfaced is this: if we didn`t have any room for increased government spending over the many last years, why is it that we do now? And for how long can we keep spending in this way to help us get out of such crises?

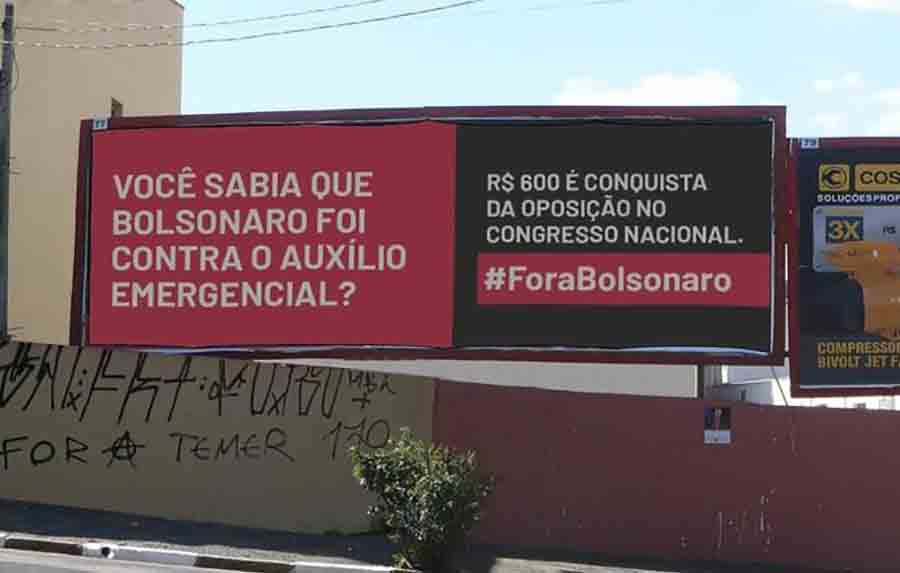

Of course, there are certain limits for these new advocates of a more active government role. Most of them want the spending bonanza to finish at the end of the year, and to then return to our austerity measures. However, civil society and some left-wing parties are trying to capitalize on this small window of opportunity to promote real change. It is very important to keep in mind that Brazil was already in a deep economic crisis (and has been since 2014) and the response to this crisis by the government was with austerity measures. In this regard, a cash transfer program that continues until the current crisis ceases and a progressive tax reform – currently the main asks of the civil society – are not meant to only respond to COVID-19, but also the wider social, political and economic crisis. This crisis that has reversed some of the gains achieved in the 2000s in Brazil, both in terms of reductions in inequality and increases in access to the labor market.

It has been a tough ride for Brazilian civil society's organizations fighting for human rights since the beginning of the Bolsonaro's government. NGOs and social movements are considered communist threats, indigenous movements are facing growing government-sanctioned acts of violence against the forests and its peoples. And the face of the pandemic, the government is looking to implement anti-gender and anti-feminist policies as a distraction from the overwhelming health and economic crises facing the country. Nevertheless, these civil society organizations have taken all of these attacks as a way to reunite. The "There Is No Money" discourse is slowly being understood as the facade that it is, and we are ready to fight even harder for human rights and fiscal justice.

CESR has worked with partners in Brazil for a number of years to challenge unjust fiscal policy measures, which were having a devastating impact on rights enjoyment even before the pandemic. In 2017, CESR collaborated with the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies (INESC) and Oxfam Brasil to analyze and visualize the likely human rights impacts of the Expenditure Ceiling and related austerity measures. CESR has also signed its support to the amicus curiae brief recently filed by Brazilian civil society against the Expenditure Ceiling. In addition, CESR is working with partners in Brazil and the wider region (including INESC) to elaborate a set of Principles & Guidelines on fiscal policy and human rights. For more on CESR’s work and partners in Brazil, see here.